Practical Psychology: What Works and What’s Nuts

Have you ever been in a relationship in which you felt ‘who you are’ was slip-slipping away? Maybe you stopped seeing your friends or family as often. Or you changed the way you dressed or the way you ordered from a menu. Not because anyone ‘made’ you, because it was just easier. Then one day you realized you’ve lost the best parts of ‘who you are?’

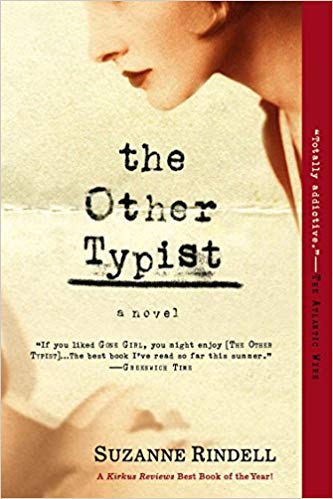

“The Other Typist” by Suzanne Rindell (spoiler warning)

Rose Baker, the lead character in Suzanne Ridell’s novel, is a woman who has no sense of her own thoughts, beliefs, or goals. Like the immature human cell without firm walls can be absorbed by a nearby mature cell with strong walls– when the powerful and psychopathic bombshell Odalie comes into Rose’s life, she is absorbed so completely—that Rose, perfect ‘good girl’ Rose–ends up taking the wrap for murder.

The Other Typist is set in 1924 when the battle for women’s rights was being to fester. Rose, however, is well aware of the confusion and disorder ‘those women’ are causing by laying claim to jobs and roles rightfully the territory of men only. She considers working as a typist at a police precinct station in Manhattan to be a daring enough move for her lifetime. Rose plans on hiding behind her typewriter, unchanged and unchallenged, for the rest of her life.

Rose grew up in an orphanage surrounded by nuns who appreciated her non-thinking identity as a super-moral, unremarkable person. As Rose explains, “I’ve always been the sort of individual to live her life by the rules. . . over the years I’ve taken a series of rules to serve as my mother, my father, my siblings, even my lovers . . . . Rules kept me safe.”

Her unexamined sense of virtue is a perfect fit for her role as a typist. “We typists,” she explains, “are considered an extension of the typewriter and the mechanical neutrality it produces. . . . We are thought to be mere receptors, passive and wonderfully incapable of deviation.” (Now who wouldn’t want a woman like that?) Rose sees her physical plainness as a virtue, part of being unproblematic, never late, never complaining, an ever-interchangeable, living machine that mechanically and perfectly transcribes recordings and leaves the thinking to others.

Rose is particularly careful to wrap herself in her “moral plain-person-lady” identity when it comes to sexual issues. While she experiences some confusing excitement when hearing the confessions of sexual predators and when a certain police officer comes in the room, Rose is quick to swish these feelings away and return to being the ‘interchangeable typist.’ Rose is convinced that, like the nuns, the station officers also appreciate her bland reliability.

At least Rose’s ‘virtue’ worked to keep her safe until the Other Typist, the not-plain Odalie Lazare joins the typing pool. Though she calls on her well-honed moral superiority to keep her away, Rose, along with everyone in the office is captured by the arousal Odalie creates whenever she walks in the room. Odalie, flashing the latest fashions, moves about the precinct office with a flounce that declares, ‘here I am and it matters what I think.’ Rose has always been careful to dress modestly, especially after the police chief remarked that “today’s modern fashions are proof of our nation’s degeneration.”

And then—Rose’s dull life takes off into the stratosphere when Odalie, who could have anyone (and does), chooses Rose to be her friend. While Odalie oozes sexuality, Rose’s attraction is not romantic and, no matter, Odalie has plenty of men to please her. Rose, without a sense of herself, would have collapsed and molded with any man or woman who chose her. Anyway, Odalie has a different plan for Rose.

Odalie introduces Rose to speakeasies, alcohol binges, fine dining, and luxurious living of all sorts. Rose moves into Odalie’s deluxe apartment. The friendship deepens, at least for Rose. The closeness suits Odalie’s purposes, too. Odalie always has someone like Rose. A plain friend. Someone who will do her bidding all the time thinking she is deciding for herself. Rose doesn’t realize it, but she’s an interchangeable part again. Instead of being a non-thinking, obey orders typist, she is a non-thinking, obey orders appendage of Odalie.

Odalie lies. About everything. Odalie has that amazing skill of the self-centered person who always convinces herself and others that her needs are more important than the needs of others. Over and over Rose says ‘yes’ when she means ‘no’ as the guidelines absorbed (but not chosen) in her childhood are switched out for a new slate to meet Odalie’s needs as easily as a restaurant list of daily specials is switched out of a menu.

Eventually, Odalie’s murderous past catches up with her. She plants Rose to take the fall for the killing she ‘needs’ to happen so that she can continue her free-wheeling life because her living free is more important than Rose’s freedom. Surely Rose will understand that. Rose made the mistake we humans often make when encountering the ‘Odalies of this world.’ She saw the way Odalie treated other people, but she believed Odalie’s words over her own experience and believed she would be an exception when the time came. Odalie would never treat her the way she treated others.

Rose ends up with a permanent stay in a mental hospital.

Rose’s story reminds me of the husband who’d become a human pretzel to keep his gorgeous, brilliant, and powerful wife. After giving himself the assignment to reclaim something of his life– he returned to therapy to report that he’d convinced her not to call her boyfriends from bed after ten o’clock. And there was the wife who’d come in convinced that if she did not agree to a threesome, she was the selfish person her husband insisted she was.

Please do not judge us humans. If you think you would never fall into the grasp of a charming psychopath, you simply don’t know how good they are at what they do.