Emotions: Living in the Now or ‘How to Visualize Whirled Peas’

Emotions: Living in the Now or ‘How to Visualize Whirled Peas’

Emotions: The Old Man, His Mop, and His Gift

How do you ‘live in the now’ when life takes a dive suddenly and forever? And you’re a kid?

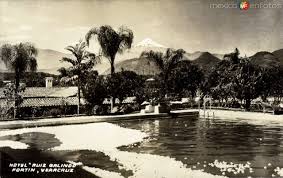

The Ruiz Gallindo Hotel is nestled in Fortín de la Flores, a little town between Veracruz, and Mexico City. It is three weeks after my mother died with an asthma attack. My father had gathered up my younger and me to wander Mexico for the summer.

The Ruiz Gallindo Hotel is nestled in Fortín de la Flores, a little town between Veracruz, and Mexico City. It is three weeks after my mother died with an asthma attack. My father had gathered up my younger and me to wander Mexico for the summer.

Talking was hard. Sleeping impossible. We made it because we were the introvert-feelings-avoiders in the family. Without my mother and older sister to bring up the obvious, we, the stoic three (half Danish), escaped quite well, or so it appear to others around the pool who assumed we were on a fun vacation.

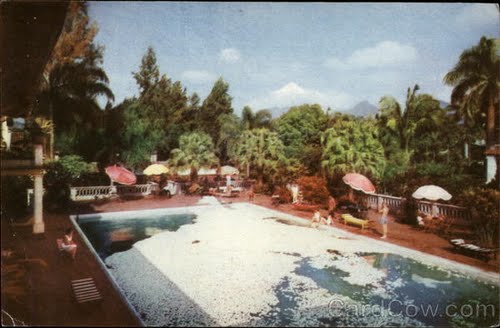

Fortín de la Flores. Fresh gardenias, the white stars of the town, are sprinkled on the surface of the swimming pool every morning. The founder of the hotel, Ruiz Galindo, an influential man who fought for the rights of the farmers, was a sort of Noah of plants. His goal was to have two (male and female) of every plant on Earth. Along with touring the hotel’s immense botanical garden, guests were welcome to ride through the jungle to Galindo’s coffee finca.

We did everything we could to stay on the move. Because, when the action slowed the terrible questions took advantage. I was vulnerable when I was alone and I’m sure it was the same for my father and brother.

On the Fortín de la Flores afternoon when the when man with the mop changed my life, I was on the bed in my room-face to the wall. Though windows were open onto the square courtyard surrounding the pool, the hotel was quiet beyond the birds in cages and far off voices speaking Spanish in the distance now and then.

On the Fortín de la Flores afternoon when the when man with the mop changed my life, I was on the bed in my room-face to the wall. Though windows were open onto the square courtyard surrounding the pool, the hotel was quiet beyond the birds in cages and far off voices speaking Spanish in the distance now and then.

The questions saw the open field and roared into my room.

What do we do now? What happens to our family? Will we ever be happy again? What about holidays, weddings, and babies? Can we make it without the heart of our family? How do I help my father? What’s this pressure in my chest? Am I having a heart attack? What happens if I have a heart attack in this remote hotel? What happens when you die?

That’s when I heard the thump of something against the wall. What made that noise? I froze and listened. The thump registered against the walls again and again at regular intervals. I took a peek.

The old man’s job was to keep the courtyard-patio clean. To make sure no dust, no dead gardenia petals settled on the tile. But there was something about the ‘way’ he worked that held my attention and slowed my panic.

The first thing I noticed was that he wasn’t in a hurry. He wasn’t focused on getting the job over with. He wasn’t anxiously struggling to figure out his future, not struggling to be efficient, not struggling to come up with a plan to save himself from returning to the simple job, not struggling to foresee the dangerous potholes ahead. Not struggling to come up with a plan to save those he loved from dealing with life as it’s dealt.

The old man, thin and slightly bent, didn’t even need to song or music. He just was. Content.

The old man, thin and slightly bent, didn’t even need to song or music. He just was. Content.

I flipped over on my back and listened without hurry. Prayed and listened. I listened and rested for several hours until diners chattered gathering at poolside tables for evening cocktails. I don’t remember how much longer he mopped, but I know my stranger’s ‘way of doing life’ had seeped somehow into my panicked teenage heart.

I had the thought that while I couldn’t change what had happened, it still mattered how I moved back and forth across the tiles in front of me. His way of being brought the first peace I’d known since our family ended. Thank you, my friend.

It’s not ‘what’ you do, it’s ‘how’ you do it.

It’s not about the product or the check. It’s the moment to moment. It’s not about the book, the house, or the kingdom. All you have is what you experienced along the way. Now.

**Note for history and culture junkies like me.

San Antonio Ruiz Galindo, the patron of Fortín del las Flores and the builder of the Ruiz Galindo estate was a pretty special guy back after the Revolution working to help peasant farmers to keep the land awarded them in the form of ejidos which means communal subsistence farms. Much like recent efforts toward ‘sustainability,’ the owners of the ejidos only asked for the privilege to use the land to take care of their families as they had for centuries.